As someone who teaches coursework that tend to lean towards the somewhat physical, I am used to getting questions from potential students about that physicality. I am also used to hearing from people who are not and never will be students list all the excuses about why they will not train in such a class.

Whenever I talk about the need for this material, or post a video about it, there is the inevitable pushback from people along the following lines: “That is all well and good to say we need to train this way but I am XYZ……” Generally it is some variation of “I am too injured, too old, too crippled, worried about getting hurt and paying for medical treatment, etc…”

And I understand that, I truly do. The harsh truth though is that the person who we have to most worry about – the violent criminal attacker, or his buddies, or the mob in the middle of a riot, or the terrorist, and so on – does not give a flying bag of feces about your reasons or rationalizations. He is not going to start to assault you and then realize you cannot physically fight back and then stops his assault. As a matter of fact, your physical issues make it more likely he is going to select you as a victim.

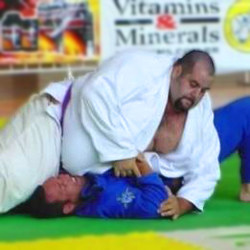

One of the most important yet overlooked parts of self-preservation is getting you deselected as a victim before anything happens. Projecting an aura of some physical capability is a damn fine way to do that. Rather than running from working to build that capability in even a minimal way is a terrible strategy. The idea is to do what you can to the best ability that you can. You may not be a BJJ black belt world champion, or world class Olympic lifter, or a Golden Gloves boxer, but having any physical fighting ability is better than having none.

As to the issue of actually dealing with doing some physical actions in a class, or pushing your strength and fitness limits, it is irrelevant. I know of no legitimate teacher of this sort of thing who expects everyone student to perform at a professional athlete level. I certainly don’t, and I know my brothers in the Shivworks Collective don’t either. Not do excellent teachers like Chuck Haggard, Greg Ellifritz, Guy Schnitzler, Steve Moses, Ben of Redbeard Combatives, or the other handful of real instructors out there.

If you have to sit out a few minutes, or have to not do a particular technique or drill, not one of us will say a negative word. On the contrary, we will all do what we can to make sure you are still getting the maximum out of the class and the material. Instead of being made fun of, you will get the same coaching that the star fighter in the class gets. That is an absolute, written in stone guarantee.

So don’t worry about whatever limitation you think you have. Come and take ECQC, or my class, or Paul Sharp’s MDOC, et al, and do what you can as well as you are able, and make yourself that much more capable. And we will do everything we can to help you achieve that.