I realize I have already covered the concept of simplicity of the manual of operations of a revolver being a major positive in the last installment of this series, but I am going to revisit it in a slightly different way.

As I pointed out in the previous entry, the simplicity of working a wheelgun is a great advantage to the non-enthusiast. In the words of Daryl Bolke, it is much more forgiving of mistakes in handling. While we know as dedicated gun users and hobbyists the Cardinal Rules of Gun Safety, people new to this may not have them ingrained in their consciousness. And before someone out there gets on their sanctimonious horse and lectures others about knowing the rules, we all know someone who at some point who should know better violated one or more of them. And look in the mirror, there is a very good chance you did at some point as well. Even if it was only in a small way, and no one got hurt, you still violated them. So let’s not throw rocks in our glass house.

However, there is another aspect to this simplicity that is entirely overlooked, even at times by the pro-revolver crowd. Do you know when simplicity is the most important thing? Where the beauty of it is at it’s highest level? Under stress.

Stress is when we are most likely to make mistakes. Stress is when the brain is shutting down and all the varied physical actions we need to take during it – steering a car safely when hydroplaning, making sure we are in a supported structure during a sudden earthquake, remembering to swim steadily when caught in a powerful riptide, etc. – and the more complex actions we have to take in those moments, the more likely they are to fail. Even heavy amounts of training in those physical actions.

At this point in my 45+ year journey in the world of applied violence, I have been a participant in, an assistant instructor in, or the head instructor in over 10,000 hours of force-on-force training evolutions. I have also been a high level competitor in many different combat sports – from boxing smokers at Top Level Gym in Phoenix, to state level judo tournaments, and international level jiujitsu events – and won a decent share of them. I unfortunately also have been involved in some real world violence. I don’t talk about any of it publicly because it becomes a lot of “he said/she said”, and there is too much of the B.S. in the fighting world, so I choose to not add to it. Suffice it to say I am not an academic when it comes to fighting.

I cannot begin to express how many times I have witnessed experienced and trained people fail miserably at basic physical actions under real or simulated life-and-death stress. Actions that you know for a fact they can do, and have done countless times in practice, then mysteriously disappears under stress. Pointing guns at people when there is no legal justification, touching their fingers to the trigger before there is any shooting cycle available, draw strokes becoming something that looks like casting a fishing pole, and on and on all occur again, and again, and again.

Having seen this countless times, I have become a strong proponent of doing the simplest things possible. Sure, we need to practice them to where there is automaticity (thanks to John Hearne for that great term), but the less the complexity of the actions in the first place, the easier and the sooner we can build automaticity, and the less chance we fumble under stress.

And what is a greater level of stress than trying to engage in a gunfight for your life? Is it not easy to imagine that under that level of pressure, the more complex and varied the actions needed to stay in the gunfight, the greater the risk that something fails? Is it not a good idea that we have as simple and as robust actions as possible?

The best firearms instructors on the planet like Tom Givens will preach and teach endlessly about this very fact, and will do all that they can to impart the most direct process possible to fix stoppages, reload, change hands, draw, re-holster, etc. Every bit of smart instructorship is geared this way.

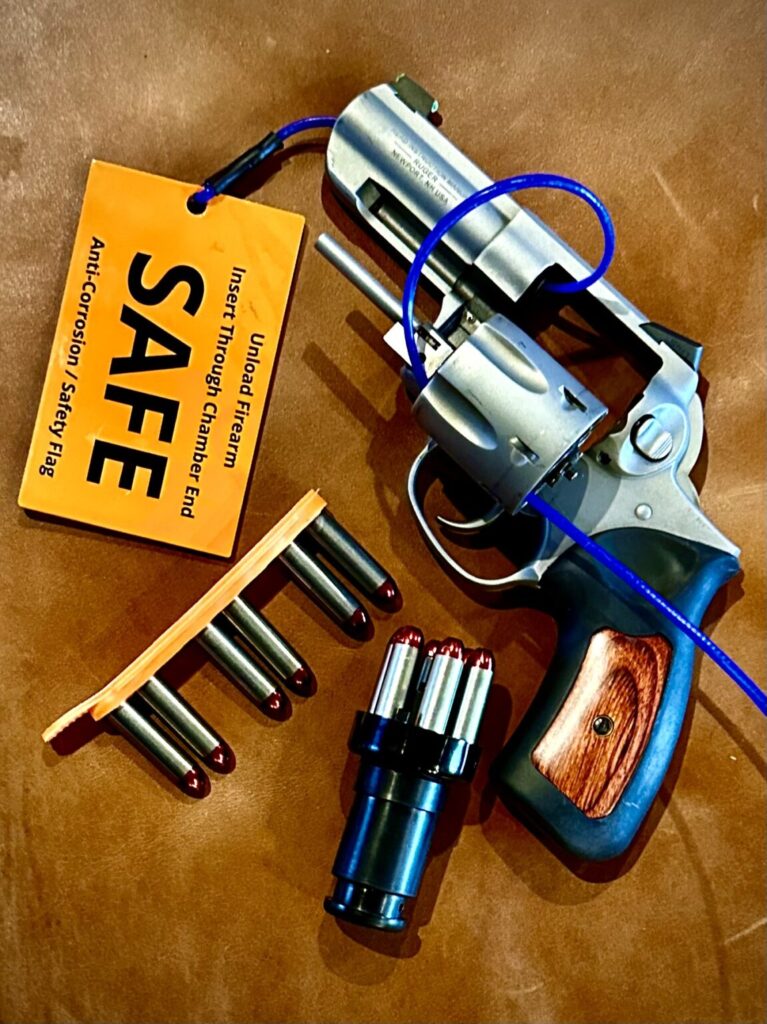

And on that note, what is more simple than working a revolver? As I noted in the previous installment, the manual of operations of a wheelgun is as simple and as robust as it gets. Outside of a catastrophic mechanical failure or an epic ammo issue, opening the cylinder, dumping out rounds, loading fresh ones and then closing the cylinder takes care of every other issue. The very definition of simplicity. Which is a pretty good idea in a gunfight.